Kala Paridrishya 2025

This

is a special exhibition that brings together a cohort of artists who completed

their master’s degrees at Kala Bhavana. The batch of 1983-85, almost all of

them, is exhibiting together four decades after leaving Santiniketan. Many of

them are established artists today; some have an international presence, and

several have made their mark as teachers, shaping the next generation of

artists in institutions across the country. The rich diversity of their work

will undoubtedly catch the viewers’ attention, but it is their alma mater that

brings them together in this exhibition. Even their evident diversity owes

something to being trained in Santiniketan. Rabindranath did not want

Santiniketan to be just another teaching institution; he wanted learning to be

liberating, enabling one to live and be creative in joyful freedom. So did Kala

Bhavana’s early teachers, and they passed that legacy on to all those who came

later in some measure.

Thus,

there is both a perceptible and imperceptible side to this exhibition. Though

they are interlinked, they also have their independence. The perceptible,

defined by the formal and thematic content of the works, can be, and will be,

savoured and measured independently by the viewers, but the imperceptible that

brings these artists together would not be as evident to the viewers and needs

underscoring. The imperceptible too has two sides to it. One is universal, the

bond established between batchmates, and the other is more specific to this

case. Let us now turn to the universal aspect of the bond that underlies this

exhibition.

Our

years in college as young adults have a special place in our lives and

memories. Reunions are often occasioned by the desire to relive that earlier

and happier moment of camaraderie. But in the case of artists, there is more

than camaraderie in the usual sense. An art college is not merely a space where

young people gather to sharpen their skills under the guidance of teachers, but

also a place where they participate in a shared adventure of self-discovery and

self-formation. The institution and the teachers play a role, but they don’t

provide an escalator that effortlessly transports one to the top. Their role is

akin to the terrain a group of trekkers chooses to explore, the mountain they

select to climb, or the river they decide to raft through. They provide

opportunities and an atmosphere, but also set challenges. It is by navigating

these opportunities and challenges that each one finds their path. Finding

one’s individual path is important in the creative arts, but having others

around you who are engaged in a similar search is both encouraging and

essential. Being thrown together with others in a similar pursuit is part of

the institution’s enabling atmosphere. This coming together is thus a

celebration of a collective adventure they were once part of, which helped set

them off on their individual paths.

While

there is nothing unusual about feeling beholden to their alma mater, it is a

little different in the case of Santiniketan. To its alumni, Santiniketan is

not merely an academic apparatus but a place, a geography that shaped them.

That adds another dimension to their bonding. For those who have lived in

Santiniketan, it is an emotion more than the institution. Its campus song,

written by Rabindranath in 1912, celebrates not the academic nurture it

provides, even as that is substantial, but the enchanting experience of nature

Santiniketan offers. This emotion is written into the hearts of people who

spend time there, and as the song claims, it becomes an emotional bond that

tugs at your heart, no matter how far you travel. The place becomes amader Santiniketan

– our Santiniketan – as the title of several reminiscences by its ex-students

suggests.

This

exhibition then brings together personal and institutional histories, bolstered

by an emotion that nurtured these artists in their youth and kept alive across

the decades. And I join them in this celebratory reunion by writing about what

holds them together, because in 1983, when they first came together, I was a

young teacher embarking on a new phase in my career, and I was almost as young

as they were. Since then, we have been fellow travellers on two parallel

tracks, and I share some of their sense of shared adventure and emotion.

Hopefully, the viewers will also get a glimpse of that as they enjoy the

pleasures of viewing art.

- R.

Shiva Kumar

(विचार, रूपाकार और प्रतिरोध के साथ साठ वर्ष)

डॉ ज्योतिष जोशी

धूमीमल कला दीर्घा, नई दिल्ली द्वारा

गत 4 अक्टूबर को ख्यात चित्रकार और कला पारखी श्री अशोक भौमिक के चित्रों की

सिंहावलोकन प्रदर्शनी बीकानेर हाउस में शुरू हुई जो 15 अक्टूबर, 2025 तक चलेगी।

प्रदर्शनी का संयोजन चर्चित छापा चित्रकार और कला अध्यापक श्री राजन श्रीपद फुलारी

ने बहुत सुरुचि और मनोयोग से किया है। प्रदर्शनी कई मायनों में महत्वपूर्ण है।

इसके महत्व का एक विशेष कारण तो यही है कि यह श्री अशोक भौमिक के विगत साठ वर्षों

की रचनात्मक यात्रा का सिंहावलोकन है। इस यात्रा की शुरुआत कहानी लिखने, कविताओं पर चित्र

बनाने और नाटक के मंच तैयार करने के साथ उसके लिए जनसम्पर्क करने तक विस्तृत रही।

कहानी और कविता की दुनिया में एक जीवंत और सृजनात्मक आकांक्षा के साथ यह स्वप्न भी

जुड़ा था कि एक ऐसा नागरिक समाज बनेगा जो समावेशी व्यवस्था का हिस्सा हो। नाटक - रंगमंच के क्षेत्र में बादल सरकार के 'थर्ड थिएटर ' यानी तीसरा रंगमंच

का अभियान केवल अभियान न था,

बल्कि वह एक बड़ा आंदोलन था जिसमें आधुनिकता के नाम पर चल रहे विक्टोरियन थिएटर

और परम्परा के नाम पर चलायमान शास्त्रीय रंगमंच से विलग रहकर एक ऐसे रंगमंच की

स्थापना का संकल्प था जो सबके लिए सुलभ हो और सबके सपनों को फलीभूत करता हो। अशोक

भौमिक इस जनपक्षधर रंगमंच और प्रगतिकामी साहित्य के सक्रिय लोगों में रहे हैं। यह

अकारण नहीं है कि उनकी इस विस्तृत कलायात्रा को विचार, रूपाकार और

प्रतिरोध से अभिहित किया गया है। उनका एक भरा पूरा व्यक्तित्व एक लेखक का भी है जो

उपन्यास, कहानी और

संस्मरण लिखते रहे हैं और उस विचार को जीते रहे हैं जिसने उनकी कला को भी जरूरी

पाथेय दिए हैं। उनकी कला की यह बेहद जरूरी पृष्ठभूमि है जिसे जाने बिना उनके कामों

को समझने का दावा करना अर्थहीन है।

कोकोरो कला वीथिका, लखनऊ

27 सितम्बर से 18 अक्टूबर 2025

राजेन्द्र प्रसाद के वाश चित्र

अवधेश मिश्र

सदैव से ही लखनऊ अपनी

कला और शिल्पों के लिए जाना जाता रहा है। यहाँ कला की

विभिन्न शैलियों और विविध शिल्परूपों ने नवस्वरुप ले समय-समय पर इस नगर और प्रदेश

को संपन्न किया है। वाश चित्रण विधा भी उन्हीं में से एक है, जिसने बीसवीं सदी के

तीसरे दशक में असित कुमार हालदार की तूलिका से लखनऊ में प्रादुर्भूत हो, फली-फूली

और पूरी दुनिया में एक जगह बनाई। असित कुमार हालदार, सुकुमार बोस, हरिहर लाल मेढ़,

सुखवीर सिंह सिंघल, फ्रैंक वेस्ली, नलिनी कुमार मिश्र और बद्रीनाथ आर्य की कला

साधना के साथ एक ऐतिहासिक यात्रा करते हुए वाश चित्रण विधा, अपनी समस्त संभावनाओं

के साथ अनेक रूपों में, लखनऊ और इसके बाहर अपना सुवास विखेरती रही.

बद्रीनाथ आर्य के शिष्य

राजेंद्र प्रसाद ने, अग्रजों एवं कला गुरुओं द्वारा की गयी वाश चित्रण विधा की

पूरी यात्रा से आगे बढ़कर विषय और तकनीकगत प्रयोग किया। आज इस नगर ही नहीं पूरे कला

जगत में अपने ढंग के काम करने वाले कलाकारों में राजेंद्र अलग पहचान रखते हैं।

राजेंद्र प्रसाद

गोरखपुर जिले के गाँव बिस्टौली के रहने वाले हैं, पिताजी किसान हैं और इनकी कला

शिक्षा, कला एवं शिल्प महाविद्यालय, लखनऊ में हुयी। कला-साधना में ग्रामीणजन-जीवन

से लेकर धार्मिक आस्थाओं से और संस्कारों से जुड़े विषय चित्र-फलक पर आकार लेते रहे।

कलाचार्य बद्रीनाथ आर्य के सान्निध्य में किये गए कामों की गति के कारण लम्बे समय

तक राजेंद्र प्रसाद ने वाश परंपरा को समृद्ध किया पर बीसवीं सदी के अंतिम दशक में

बुद्धत्व की और मुड़े और एक नयी शैली में काम करने लगे।

आरंभिक कामों में दैनिक जीवन, जैसे - रस्सी बटता बुज़ुर्ग, जाल डालता मछुवारा, पिया की प्रतीक्षा करती युवती, खेत में काम करते किसान, प्राकृतिक दृश्य - बारिश, दृश्य चित्रों के साथ आराम फरमा रहे बंदरों की टोली, धार्मिक चित्रों में - सूर्य को जल चढ़ाती युवती, मरघट पर राजा हरिश्चंद्र, अयोध्या में नाव पर बैठे बन्दर, समाधिस्त भगवान राम, अयोध्या में सिंघासन पर रखे खड़ाऊँ की पूजा करते भरत, लार्ड कृष्णा आदि प्रमुख हैं। इसके अतिरिक्त राजेंद्र ने आतंकवाद को भी अपनी अभिव्यक्ति का विषय बनाया। महानिर्वाण शीर्षक से बनाया गया चित्र जो गांधीजी की हत्या से सम्बंधित था, काफी लोकप्रिय रहा।

लगभग 1994 के आसपास राजेंद्र

प्रसाद ने अपनी शैली बदली और मानवाकृतियों की शारीरिक संरचना को विशेष महत्त्व

देते हुए पट्टीदार आवरण चित्रित किया जो दक्ष हाथों से ही किया जा सकता था। यहीं

से राजेन्द्र की एक अलग पहचान बनती है। यह लखनऊ-वाश का विस्तार कहा जा सकता है,

जिसमें विषय और चित्रण विधि बदली हुयी है। और यही इनकी बुद्ध शृंखला का भी आधार है। इस शृंखला के चित्र परम्परागत

पैलेट से अलग हैं। शारीरिक संरचना और विषय-वस्तु भी ध्यातव्य। मुख के स्थान पर या

तो मुखौटा है या ऊपरी हिस्सा खोखला। देखते और आस्वाद करते समय सबके अपने निहितार्थ

हो सकते हैं। राजेंद्र प्रसाद वैसे तो अपनी शैली गत

विशेषताओं के अनुसार बद्रीनाथ आर्य के काफी निकट रहे हैं पर समकालीन कला

प्रवृत्तियों की अनदेखी कभी नहीं किया बल्कि लोगों में भी उन्होंने अपने को अद्यतन

और लखनऊ के अन्य समकालीन कलाकारों के समानांतर ही रखा। उन्होंने वाश तकनीक के

अतिरिक्त तैल रंग में एक शैली विकसित की, एक हस्ताक्षर

बनाया, जो उनकी पहचान बन सका। इस शृंखला में सिर विहीन या

खोखले सिरों वाली एक आकृति विकसित की जिसका मांसल और स्वस्थ शरीर होता है, यही राजेंद्र के संयोजन ओं का मुख्य पात्र होता है इन्हीं पात्रों और

संयोजनों द्वारा राजेंद्र अनेक विषयों-

समसामयिक, सामाजिक, राजनीतिक घटनाओं,

विचारों का नाटकीय प्रभाव वाला चित्र खींचते हैं, एक जागरूक नागरिक और कलाकार के रूप में अपने दायित्वों को महसूस करते हुए

चित्रों के जरिए समय समय पर अपनी बात कहते हैं।

राजेंद्र मुख्य रूप से

लखनऊ की उस कला धारा के कलाकार हैं, जिससे असित

हलदार, बीएन मुखर्जी, हरिहर लाल मेढ़,

सुखवीर सिंघल, नलिनी कुमार मिश्र, फ्रैंक वेस्ली, नित्यानंद महापात्र, बद्रीनाथ आर्य आदि कलाकारों ने पोषित किया है, पर उस

कलाधारा और शैली से बिल्कुल बंधकर राजेंद्र ने कार्य नहीं किया, बल्कि उसके समानांतर ही एक शैली विकसित कर ली और प्रयोगधर्मी कलाकारों की

श्रेणी में भी महत्वपूर्ण हो गए।

राजेंद्र 02 अक्टूबर

1958 में गोरखपुर, उत्तर प्रदेश में जन्मे थे.

वहीं इनकी प्रारंभिक शिक्षा-दीक्षा हुयी. खेत - खलिहान, बाग

- बगीचे में खेले - बढ़े, उन संस्कारों में जिए, जो भारतवर्ष की आत्मा के रूप में जाने जाते हैं. ग्रामीण जीवन की दैनिक

गतिविधियों रीति-रिवाजों, मेले - ठेले, मांगलिक आयोजन, उत्सव - त्यौहारों, रिश्तों - नातों, सहिष्णुता - सदाचार और अन्तर्सम्बन्धों

को महसूस किया, आत्मसात किया जो उनके चित्र- विषय के रूप में

अभिव्यक्त होने लगे।

वाश चित्रों की शृंखला

में राजेंद्र ने सारंगी वाला सुंदर संयोजन बनाया है। पेड़ के चबूतरे पर बैठा

सारंगी वाला गाना गा रहा है। चबूतरा सुंदर पत्थरों से जोड़ा गया है। सामने कुछ लोग

बैठे तल्लीनता से संगीत का आनंद ले रहे हैं। हल को उल्टा कर उसमें पेट्रोमैक्स

टांगा गया है, जिसका हल्का उजाला सभी और फैल रहा है।

प्रकाश, दरवाजे से वोट लिए खड़ी महिला पर भी पड़ रहा है,

जो गाल पर हाथ लगाए बिल्कुल रिलैक्स होकर खड़ी है, सारंगी वाले के कपड़े, दाढ़ी उसके हाव-भाव बगल में

रखे बिस्तरबंद, सामने बैठे श्रोतागण के कपड़ों की सिलवटें और

नारी आकृति में कपड़ों पर सूक्ष्म अंकन, डिटेल फिनिशिंग,

उजाले का समुचित फैलाव और मध्यम तानों में पूरे चित्र पर किया गया

रंग व्यवहार दर्शनीय है।

ये विषय उनके पात्रों

की प्रकृति, विषय के अनुसार इन क्षणों का सूक्ष्म अंकन,

वाश तकनीक की विशेषताएं - रंगो का माधुर्य, तानों

का वैविध्य, धूसर वातावरण में प्रकाशित वस्तुओं, पात्रों पर छाया - प्रकाश का सुंदर खेल व विषयानुसार रंग - योजना यह सब

जहां शिल्पगत दक्षता व रचनात्मकता का प्रमाण है, वहीं भारतीय

लोक -जनसामान्य के जीवन से जुड़े अनेक पहलुओं के प्रति पैनी दृष्टि के परिचायक भी।

ऐसे विषयों में

राजेंद्र ने राधा - कृष्ण, सरस्वती, लक्ष्मी,

शिव आदि धार्मिक विषय, पौराणिक संदर्भ रामायण

- महाभारत के कथानकों पर आधारित सामाजिक व ग्राम्य विषय - मचान पर बैठे रखवाली

करते लोग, मचान पर रस्सी बटते लोग, कूदती

- फांदती - उछलती - खेतों में युवतियां, प्रतीक्षा, बाग में खेल खेलती बालाएं, शृंगार करती नायिका,

हुक्का पीते गांव के बड़े बुजुर्ग, पंचायत आदि

का बड़ा ही मार्मिक चित्रण वाश पेंटिंग में किया गया है।

इन वाश चित्रों के अतिरिक्त समकालीन कला धारा और प्रवृत्तियों से सक्रियता पूर्वक जुड़ने के लिए राजेंद्र ने समकालीन समस्याओं पर आधारित, राजनीतिक व्यवस्था पर कटाक्ष करती थीम पर कार्य करना प्रारंभ किया। शृंखलाएं बनाईं। अपने संयोजन के लिए एक विशेष आकृति चुनी जो खोखली खोपड़ी वाला स्वस्थ मांसल शरीर का पुरुष होता है, कभी यह पुरुष चेन की तरह आपस में जुड़ी सुरंग में घुस रहा होता है, तो कहीं वह बोझ तले दब रहा होता है। कहीं ढले हुए, कहीं बहते हुए आकार, तो कहीं इलेक्ट्रिक वायर (केबिल) कनेक्शन यह सब प्रतीक हैं, राजेंद्र के संयोजन के, जो बहते पानी पर तैर रहे होते हैं, इनकी अपनी कोई जमीन नहीं होती है। बहुत सारे ढले हुए चेहरे (मास्क) भी यत्र - तत्र रखे होते हैं, जो इस बात के संकेत हैं कि आज व्यक्ति का कोई एक चेहरा या असली चेहरा नहीं रह गया है, बल्कि सुविधा और आवश्यकतानुसार व्यक्ति अपना चेहरा और चरित्र चुन रहा है। किसी - किसी चित्र में राजेंद्र ने नारी शरीर के शोषण को प्रतीकात्मक रूप में दिखाने का प्रयास किया है। इसी तरह एक चित्र में दर्शाने का प्रयास किया है कि अण्डों से जीवन समाप्त किया जा रहा है, बल्कि उसमे जीवन आने के पहले ही व्यक्ति उसे खा ले रहा है और अण्डों से बाहर आ रहे कुछ चूजे यह सब नफ़रत से देख रहे हैं।

सामाजिक और पर्यावरणीय

समस्याओं के प्रति सचेत राजेन्द्र ने ‘बर्ड फ्लू’ पर आधारित एक चित्र बनाया है, जिसमें सिरविहीन व्यक्ति अचेत पड़ा

है और व्यक्ति के घुटने पर मुर्गा बैठा कटाक्ष कर रहा है। दृश्यभाषा और मुहाबरा

कलाकार का मौलिक है और संयोजन अति रचनात्मक। लखनऊ विश्वविद्यालय में संग्रहीत एक

अन्य चित्र में राजेंद्र ने बिल्ली से प्यार करती एक महिला को दर्शाया है, जिसकी गोंद में बिल्ली है और निर्धन - मलिन बस्ती के बच्चे लालच भरी निगाह

से उसे देख रहे हैं।

एक चित्र में

चेहराविहीन मांसल शरीर वाली नारी जो पट्टीदार कपड़े पहनी है, अलग-अलग पटरों पर पेचकस (स्क्रू ड्राईवर) से अलग-अलग तरह के चेहरे फिट कर

रही है। इनमें दो आकृतियों का पैर दिख रहा है, शेष भाग सुरंग

में है। संयोजन में नारी के स्तन जैसे आकार से धागे नीचे लटक रहे हैं, जो पानी और सुरंग पर तैरते कपड़े से बंधे हैं। इस तरह प्रतीकात्मक रूप में

छाए प्रकाश से डायमेंशन क्रिएट करते हुए यथार्थ रूप में इस शृंखला को राजेंद्र ने

रचा है।

इस तरह कहीं पुरुष

आकृति को ऐसे अजायब घर में बैठा बनाया गया है, जहां उसे अपना

ही अक्श दिख रहा है, साथ में बहुत सारे चेहरे टंगे हैं। कहीं

खोखले चेहरे वाली आकृतियां, नारी आकृतियों के ऊपर से कपड़े

हटा कर शायद समाज को किसी और सच्चाई से अवगत कराना चाहती हैं। किसी किसी चित्र में

यही आकृतियां शिलाखंडों के बोझ तले दबी हैं। माध्यमगत विशेषताओं को देखें तो

राजेंद्र तैल माध्यम को भी जलरंग - वाश की तरह ही पतले लेयर और छोटे-छोटे

स्ट्रोक्स में प्रयोग करते हैं। यह लखनऊ की विशेषता भी है, कि

यहां प्रायः कलाकारों ने तैल माध्यम को जल की ही तरह प्रयोग किया है।

राजेंद्र के पात्र -

आकृतियों को, चाहे नारी हो या पुरुष, उन्हें मांसल व बलवान या बलवती बनाया गया है, जिनमें

बहुत कुछ कर पाने की क्षमता दिखाई गई है. शायद यह परिकल्पना है - बागी और

क्रांतिकारी विचारों की या महिला सशक्तिकरण की। सभी संयोजनों में बहुत सारे चेहरे

दीवारों व पटरों पर कसे हुए या कोटरों में टंगे हुए दिखाए गए हैं। विशेषता यह है

कि इन बलवान शरीरों का मस्तिष्क को खोखला है। यानी समाज में बल और क्षमता है पर उसमें

विचार, बुद्धि और एक सकारात्मक सोच की कमी है, जिसे देने की

आवश्यकता है। राजेंद्र की संयोजनों में मुख्य संवेदन के रूप में ‘मां’ दिखाई देती

है और संयोजन के सारे पात्र जहां एक और उपन्यास सा फैलाव लिए हुए होते हैं,

वही ‘मां’ का दूध-पावस (जो शक्ति प्रदान करता है और उसका आंचल जो

सुरक्षा-संरक्षा देता है) एक सूत्र में बंधा हुआ पूरे कथानक को बांधता है।

आज के आधुनिक परिवेश

में राजेंद्र इन संयोजनों के माध्यम से ‘मां’ के महत्व को पुनर्प्रकाशित करते हैं, वहीं इसी संवेदन को केंद्र में रखकर समाज की कुरीतियों, अनाचार, विद्रूपता, विभीषिका,

आतंकवाद जैसे सामाजिक, राजनीतिक विषयों की

अपनी अभिव्यक्ति का मुख्य विषय बनाकर अपनी जागरूक उपस्थिति प्रमाणित करते हैं।

राजेंद्र का माध्यम और शैली जो भी रही हो, पर उन्होंने सदैव कला और केवल कला को जिया है - एक सच्चे कलाकार की तरह, जिन्हें दुनिया के अन्य आकर्षण बेमानी लगते हैं. वह गुरु - शिष्य की उस परंपरा का अनुसरण करते हुए भी नजर आते हैं जो बद्रीनाथ आर्य और नित्यानंद महापात्र ने बनाई है। लखनऊ विश्वविद्यालय और फिर डॉ शकुंतला मिश्रा राष्ट्रीय पुनर्वास विश्वविद्यालय में उन्होंने शिष्यों के बीच एक अच्छे गुरु की छवि बनाई है, और लोकप्रिय रहे हैं। आशा है कि इसी लोकप्रियता के साथ अपनी कला साधना करते हुए वे अपने कला अवदान से प्रदेश और देश को गौरवान्वित करेंगे।

शताब्दी की मूर्तियात्रा : एक विरल प्रदर्शनी

डॉ ज्योतिष जोशी

रज़ा फाउंडेशन और प्रोग्रेसिव आर्ट

गैलरी के संयुक्त तत्वावधान में नई दिल्ली के श्रीधरानी कला दीर्घा में गत 5 अक्टूबर, 2025 को भारतीय

मूर्तिकला की शताब्दी यात्रा पर एक मूल्यवान प्रदर्शनी का शुभारम्भ हुआ। 12 अक्टूबर तक

चलनेवाली इस प्रदर्शनी का संयोजन वसुंधरा डालमिया ने किया है। प्रदर्शनी कई

दृष्टियों से भारतीय मूर्तिशिल्प की सौ वर्षों की यात्रा को दिखाती है और बढ़ते हुए

क्रम में उसके विविध प्रयोगों से भी हमारा परिचय कराती है।

हम यह जानते हैं कि अंग्रेजी शासन के स्थापित होने के बाद सुषुप्त पड़ी भारतीय कला जागृत हुई पर उसकी दिशा बदल गई थी। पश्चिम में आधुनिक कला का उदय हो चुका था। किंतु भारत में न तो पारंपरिक नियमों पर काम हो रहा था और न उनमें कोई नवीन उद्भावना ही जन्म ले रही थी। ऐसे में ब्रिटिश शासन ने मुंबई, लाहौर,मद्रास और कोलकाता में कला विद्यालयों की स्थापना करके यूरोपीय ढंग की कला का प्रसार किया। इन विद्यालयों में प्रभाववाद, अभिव्यंजनावाद, यथार्थवाद,अति यथार्थवाद आदि कला पद्धतियों में भारतीय कलाकारों को प्रशिक्षण दिया जाने लगा था। कलाकारों के पुराने माध्यम बदले जा चुके थे जिसके परिणामस्वरूप टेराकोटा, फाइबर ग्लास, प्लास्टर ऑफ पेरिस, मोम आदि माध्यम मूर्तिकला में प्रवेश पाते गए। इसका बुरा असर यह हुआ कि पश्चिमी ढंग की यथार्थवादी मूर्तिशिल्पों की निर्मिति में तेजी आई। भारतीय शैली के आदर्शवादी मूर्तिशिल्पों की तुलना में यूरोपीय यथार्थवाद से प्रेरित मूर्तियों की मांग भी बाजार में बढ़ने लगी थी। यही स्थिति कला के दूसरे माध्यमों में भी थी।

निसंदेह भारतीय आधुनिक मूर्तिकला में

आगे शंखो चौधरी, चिंतामणि

कर, धनराज भगत,गिरीश भट्ट, ईश्वरलाल बी.

गुर्जर, जितेंद्र

कुमार, अमरनाथ

सहगल, पीलू

पोचकनवाला,सुधीर

खस्तगीर, श्रीधर महापात्र,

डी. बी. जोग, एम.

धर्माणी, भवेशचन्द्र

सान्याल, हिरण्यमय

चौधरी,प्रदोष

दासगुप्ता,सोमनाथ होर, के. जी.सुब्रमण्यम, एस. एल. पाराशर,

एस. धनपाल,ए. एच.

कुलकर्णी, पीवी जानकी

राम,महेंद्र पांड्या, हिम्मत शाह, शर्बरी रायचौधरी, बलबीर सिंह कट्ट, राघव कनेरिया, सतीश गुजराल,मीरा मुखर्जी, मृणालिनी मुखर्जी, लक्ष्मा गौड़, नंद गोपाल, बिमान बी. दास,रमेश बिष्ट, लतिका कट्ट, पुष्पमाला,एलेक्स मैथ्यू, वालसन कोलेरी, रवीन्द्र रेड्डी, एस. राधाकृष्ण, विवान सुंदरम, ध्रुव मिस्त्री आदि

मूर्तिकार आते हैं जो अपने नवाचार के कारण जाने जाते हैं। निसंदेह इनकी परंपरा

देवीप्रसाद रायचौधरी से तो जुड़ती है,

पर जिस भाव - विन्यास और कल्पनाशीलता के साथ उनके काम दृश्य होते हैं उनमें

रामकिंकर बैज की प्रेरणा मुख्य है।

कहना चाहिए कि पारंपरिक भारतीय

मूर्तिशिल्प को यदि आधुनिक बनाने का श्रेय देवीप्रसाद रायचौधरी को है,वहीं उसे कल्पनाशील तथा नवाचारी बनाने

का श्रेय रामकिंकर बैज को है। बैज ही वह मूल प्रस्थान हैं जिन्होंने मूर्तिकला को

लोक- तत्वों से जोड़ा, कल्पनाशीलता

को अभीष्ट बनाने पर बल दिया तथा मूर्ति को ज्यामितीय संरचनाओं में भी बरतने की

दिशा दी।

भारत की कला और मूर्तिशिल्प की

आधुनिकता तथा समकालीनता को जो लोग उसके विविध प्रयोगों और नवाचारों में देखना

चाहते हैं, उनके लिए

यह प्रदर्शनी अवश्य दर्शनीय है।

(चित्र सौजन्य : रफ़ीक़ शाह)

Paradigm Shift in Indian Modernism

Rabindranath Tagore and Amrita Sher-Gil

Johny ML

'Paradigm Shift in Indian Modernism: Rabindranath Tagore and

Amrita Sher-Gil' was the topic of Ashok Bhowmick's illustrated lecture at the

IIC, Delhi on 14th May. Organized by Dhoomimal Gallery, this lecture

kick-started the collateral programs of the forthcoming Retrospective of Ashok

Bhowmick at the Bikaner House in November 2025.

Veteran artist, art critic and art history researcher, Ashok Bhowmick has been interested in the above subject for quite a long time. His primary contention is that there has been a fundamental fallacy in our analysis of the Indian modern art; we 'read' a modern work of art rather than 'see' one, because of this often we tend to create stories 'about' a work of art instead of 'seeing' it, taking its formal values into consideration. Formal values, held high by a practicing artist, are often overlooked because of the patrons' 'need' for a convincing story.

Bhowmick finds a historical and socio-cultural reason for such a fallacious approach to art in India. In India, art has always been an 'illustration' of the familiar narratives. What art did to a larger section of the society which was forced to be illiterate and deprived of 'knowledge' and 'texts' due to the enforcement of caste hierarchies, was subjecting them to the narratives ingrained in the oral traditions. Hence, a work of art had the mission to 'illustrate' and 'educate' the masses. This missionary high-handedness of patrons of yore had made Indian art a field of 'illustrations'.

Illustrations are not stand alone art works. A narrative is a precondition for an illustration. Identification and empathy with a work of art were expected from the viewers based on this precondition of 'recognition' (of the story). Citing a series of examples Bhowmick established how, even during the Bengal Revivalist period, the illustrative aspect gave the fundamental framework for understanding art.

According to Bhowmick, the first significant rupture from

this 'illustrative continuity' happened with the arrival of Rabindranath Tagore

as a visual artist. Though Tagore's art did not happen in a vacuum, he was the

first one to separate his literature from his art. He wrote poems, novels,

short stories and plays but he never illustrated them. Self-referencing visual

texts happened in Tagore too but they functioned within a renewed context

completely detached from the puranic and mythological narratives.

Amrita Sher-Gil took it to the next level, according to Bhowmick by including the excluded. Though post-modernist subaltern narratives and micro-narratives where theoretically substantiated in those days Sher-Gil turned her attention to the 'people' of India and never attributed them any mythological qualities or dimensions. Besides, Bhowmick explained how the formal values of both Tagore and Sher-Gil had great distinctions as they employed softness and thickness of colors or pure avoidance of it depending on the mood and subject, which became their established styles, almost inimitable.

Rabindranath Tagore (NGMA, New Delhi)Bhowmick takes a departure from what Geeta Kapur had established in her book When was Modernism, where she found modernism in Indian art as a conjoined narrative of nationalism. Bhowmick keeps the trajectory of Indian nationalist art as an extension of the 'illustration' of the existing narratives, which was, though he did not say it in many words, 'Hindu' art or a kind of art that fell back on the resources of the newly found alternative secular streams as envisioned by the artists who came around Tagore in Santiniketan. As per Bhowmick, Tagore and Sher-Gil were the flag-bearers of Indian modernism in art, and his lecture was convincing to see that departure in perspective.

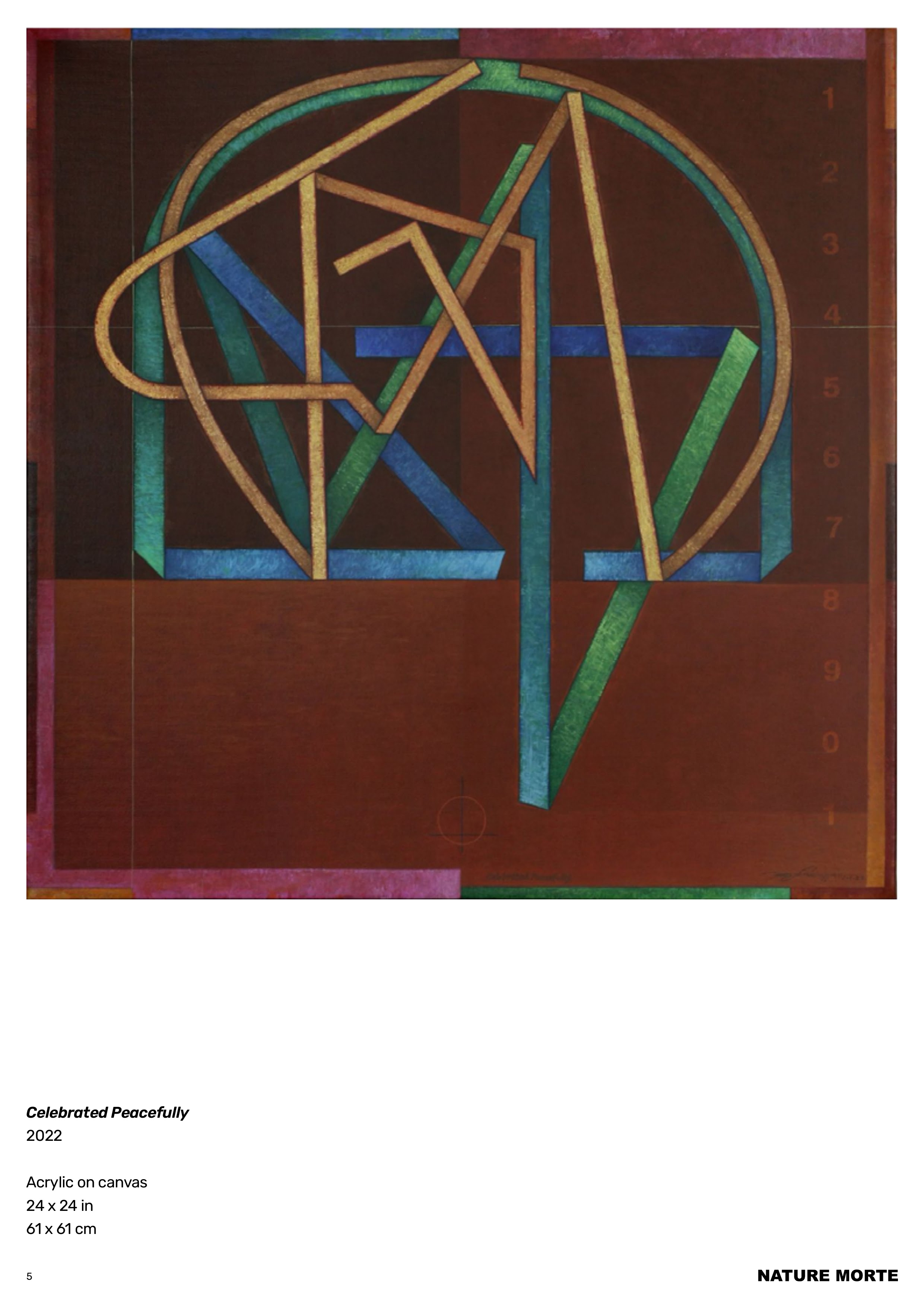

“The only true reality lies in the interaction between the physical and the psychological. I aim to capture this movement in my work.” — Rm. Palaniappan

Nature Morte is proud to present an exhibition of new works by Rm. Palaniappan. Born in 1957, Palaniappan lives and works in Chennai. His career spans more than four decades and includes a wide variety of works in all mediums, most specifically prints and works on paper. His newest works are paintings using acrylic on canvas in a variety of sizes. Each painting contains the image of tangled lines, lines that meander in multiple directions, twisting and turning in on themselves. The lines change colors as they progress, adding both substance and personality, suggesting the journey of life. The works resemble cartographies of military maneuvers as seen from above, landscapes based on a new type of geographic perspective. As the artist has said : “Only someone flying in space can make a three-dimensional drawing and stretch it to infinity, thus expressing complete human freedom.” As described by the writer Sadanand Menon: “A neutral, non-anthropomorphic space, a kind of experimental geography and the possibility of proposing radical landscapes. Images of unnamable places and their visual representations, whether terrestrial or planetary or astronomical.”

As studies of movement in space, the paintings could be said to ad dress the latest developments in physics, namely theories of Quantum Entanglement. Palaniappan’s family was involved with the commercial and graphic arts, his father being a distributor of calendar art and later his brothers owned printing and packaging companies. Palaniappan’s artistic practice from the late 1970s (when he was in art college) to the early 2000s was entirely dedicated to printmaking, collages, and graphic works on paper. This history is retained in the paintings today, as the borders of each are demarcated with contrasting colors, numbers hover in the margins, and the target devices used for registration are still present. The addition of sand to the paint creates a subtle texture in the paintings, further emphasizing their references to landscapes and cartography. In all, the artist’s interests in science, math and outer space (present since childhood and operative in his entire practice) are distilled into crystalized representations.

Rm. Palaniappan was born in Devakottai, Tamil Nadu in 1957 and has been based in Chennai since the late 1970s. He is an alumnus of the Government College of Arts and Crafts in Chennai, where he acquired a Diploma in Fine Arts, Painting in 1980 and a PG Diploma in Industrial Design, Ceramics in 1981. He studied advanced lithography at the Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA in 1991 and was an Artist in Residence at Oxford University, UK in 1996. He is a recipient of the Fulbright Grant, the Charles Wallace (India) Trust, International Visitorship program of USIS, and Senior Fellowship of the Government of India. His works have been included in group exhibitions all over the world and in India he has held solo shows of his works with the galleries Art Heritage and Nature Morte in New Delhi, Sakshi Gallery in Mumbai, Apparao Galleries in Chennai, and Gallery Sumukha in Bangalore. Palaniappan’s works are included in the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Modern Art and Lalit Kala Akademi in New Delhi, the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, Oxford University in Oxford, Cincinnati Art Museum in the US, the Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art in Kansas, US, the Library of Congress in Washington DC, the Taipei Art Museum in Taiwan, the Madras Art Museum in Chennai, and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, among others. A comprehensive retrospective of his works since 1976, entitled “Mapping the Invisible,” was hosted by Dakshinachitra Museum in Chennai from December 15, 2024 to April 4, 2025.

Uma Nair

At Bikaner House in Delhi, you have to walk up to the first floor of the Centre for Contemporary Art and savour a panoramic work of Phaneendra Nath Chaturvedi’s butterflies in a small room to know the power and passion of this brilliant artist who trained at College of Art Lucknow. Looking at his work with his professor Jai Krishna Agarwal on Saturday became a moment of deep revelations and reflections between Guru and shishya.

the butterflies flutter over the surface of the canvas, it reminds me of the world’s finest artist Yayoi Kusama’s mosaic-like shards in their spread wings, each revealing exquisite patterns of orange, red, white and blue spots. For Phaneendra, the butterfly is more than a symbol of fragility and beauty; it is a symbol of service, of selfless spiritual significance, and a metaphor for man and nature.

Nestled and sprinkled on pedestals in this room are his butterfly sculptures shining in modern steel and sculpted in the realms of technological finesse. The details and precision of the creatures’ wings in many ways fuse with Phaneendra’s own mesmeric style. Comprising an iridescent assortment of colours and hues, the sculptures bear a similarly diaphanous and lustred quality that enchants us. We gaze at the painting and the sculptures too and think of intricately tessellated backgrounds—a flattened plane of biomorphic swarms —sprawling and propagating into infinite spacelike cells under a microscope.

Repetition is Phaneendra’s elixir; he creates his own corollary with an ‘all-over’ method, the shapes evoking the enduring legacy of an infinite carnival of butterflies celebrating the ecological spectrum.

Then in the largest room on the top floor is the man with flat wings, reminding us of an aeroplane. Whatever he paints or draws or creates with pencil and pastel, each work comes alive with unique perceptual effects. In his archetypal grim grim-looking, intimate figurative imagery, each work presents the artist Phaneendra’s spectacular, pulsating vision.

Phaneendra’s fascination with the winged man is inextricable from his experience and appreciation of the world.” On earth, man is only one dot among millions of others,” he says. ” We must not forget ourselves with the desires of our burning ambition. I feel that in our everyday struggles; we lose ourselves in the ever-advancing stream of eternity.”

Take the lift and look at his winged man sculpture on the ground floor. Here he calls it Totem and you see a fiberglass sculpture of a man with an owl’s wings. Precision and perfection tell us that this modern man in a pair of impeccable trousers is a testimony to time. The artist’s pleasure in nature and its abundant variety of forms is palpable. Each individual wing, whether in a drawing on the two walls or in a single sculpture, is painstakingly rendered in both graphite as well as fiberglass. The open wings unfurl into swathes of space, exuberant in expanse.

The series he has created as clusters over the last few years are delicately articulated. We must note that the artist’s work became smoother, more orderly, figurative, and above all, more pensive. There is indeed a lightness as well as a gravitas to these subsequent paintings.

At the centre of the long corridor stands a monochromatic suited man created in mixed media on archival paper from the year 2016 titled The Good Wisher. Unpretentious and filled with a host of hidden emotions, the bouquet of flowers and caparisoned little bird on the shoulder become organic objects likely to speak to Phaneendra’s own experiences as well as memories of formative fascination for both botanical as well as zoological species.

At once, you think of the masterpiece of the Monarch Butterfly with a portrait of a suited man created in pencil and pastel, and realise that the butterfly possesses spiritual significance in Southeast Asian cultures. At once a symbol of metamorphosis and transformation, it is believed by many to transport the soul between terrestrial and celestial realms after death. Its associated mythologies pertain to Phaneendra’s own practice, his deep and enduring meditations on the self, the cosmos and eternity. His sensitivity to the fragile creature with a short life is indeed both personal as well as deeply contemplative. As soon as you savour the studies and his inbuilt and inherent sense of perfection, you realise that these brightly coloured insects further encapsulate childhood comfort and nostalgia in the beauty of his own teenage daughter.

Combining meticulous, figurative elements with the hypnotic traces of his own love for realism, this solo exhibition curated by Sanya Malik is a powerful example of Phaneendra’s visual idioms and his spellbound observations of the natural and man-made world around him.

Courtesy : TOI Blog

Hem Raj & His Art-scape

Sushma K Bahl

An amazing expanse of over a dozen mammoth paintings, immersed in dense and colourful suite of imagery appears in Hem Raj’s solo exhibition titled Eternal Reminiscence. Entailing a duality of absence and presence, the collection adorns an enigmatic look and feel. Within the framework of contemporary abstraction, a wide spectrum of non-discernible non-figurative formless forms, somewhat surrealist, appear in the artist’s free flowing creatives. There are enchanting compositions which incorporate ideas and symbols, line work, variously painted shapes and shades, dots and metaphors, calligraphy and collage. Painted in bold and fluid streaks and contours, the art works resonate with a spontaneity. Interwoven with intuition and mystique, they seem to emerge out of a metamorphic realm. Unconventional and ephemeral, the ‘non-object’ non-recognizable imagery relates to no particular form or figure, narrative or “pre-thought-out ideas or context” asserts the artist who has evolved his own distinct abstract lexicon.

Tracing Track

The place and pride that Hem Raj’s art enjoys today, has come to him through a winding track. The trajectory he has had to follow, meandered through various routes and realms before he could pursue his inborn talent in art. Neither his parents nor anyone else in the family that he grew up amidst, had any interest or affiliation with art. Hem Raj himself, passionate about creativity, had no interest in academics. He spent most of his time in class drawing and painting, and did poorly in studies at school. The father naturally got worried about his son’s future and arranged for the young boy to apprentice with a tailor. But that ended abruptly as the restless Hem Raj did not find it worthwhile. The next came his training as an electrician, which too did not last long as it could not sustain his interest. A self-inspired person passionate about art, he decided to take things in his own hands and convinced his father, that art was his calling. Helped by his art teacher at school, who was the first one to spot his talent, the young boy managed to get admission for a bachelor’s degree in painting at the College of Art in Delhi.

A similar rendezvous has been a part of his subsequent art track. Beginning with still life, it has traversed through figuration, portraiture and narrative genres. Also experimented with landscape and learnt Thangka painting. Attended workshops and art camps to network and enhance his skills. Turned finally to abstraction, in which he has created a niche for himself. The style that continues to be his destined calling, can only be categorised as an abstract oeuvre. It is this domain that brought Hem Raj his first invitation for a solo show while he was still in the final year for a master’s degree at the art college. “The exhibition received good critical feedback and people became aware of my art, but nothing got sold”, said the artist with a mixed sense of joy and dismay. Fortunately things changed fairly quickly and positively for him. Hem Raj recalls with pride the next exhibition, when three of his paintings in a group show were the first ones to get picked up by a collector. Since this first success, he and his art, has never had to look back, winning both positive appraisal and monetary gains for him and his work.

Art Aesthetics

Marked for his distinct style, art is like a soul search, an intuitive experience for Hem Raj. The emphasis in his incredible body of work is on sensuousness, mystery and lyricism. Improvising and painting, it is the force of his creative unconsciousness that brings the ideas alive as he takes up his brush, dips it in oil paint and begins working on a canvas. Devoid of conventionality he does not compose laboured or pre-planned pictures. Instead plays in free abundance with discrete elements to create some unexpected unstructured but effective surrealist abstract visuals. Unveiling the un-manifest, his formless forms bring forth the unknown. The aesthetics of his work engages with undefinable mysterious erotic forms, that engross not only the retina, but also the mind soul and emotions of the viewer.

Another interesting feature of Hem Raj’s art and aesthetics is the incorporation of decorative elements in the milieu of his unequivocally Indian, spontaneous and timeless work. His creatives can be traced to the country’s ancient roots in tantric, tribal and craft traditions. Embracing concepts around cycle of life, planetary movements, changing seasons, fertility and divine metaphors such as lingam, Bindu (symbolising Shiva’s third eye) and totem pole. His masterly pieces in abstract and geometric renditions invoke a spiritual aura. His forms are expressive but not realistic. Equally inspired by modern masters of Indian art such as VS Gaitonde, SH Raza, Ram Kumar and their contemporaries, he has also studied the work of Western abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock, Paul Klee, Joan Miro and others. However much of his art style is distinctly his own, which he has evolved over time, “guided by my teachers Jai Zharotia and Rajesh Mehra”.

He enjoys painting in oil on canvas, does not like acrylic as “acrylic paint gets lighter with time and loses its sheen” opines the artist. Water colours are used sparingly and only for smaller works. He opts for larger, more often enormous sized canvases. On his preference is for oil paints and larger canvases he asserts “they allow me more space for a free play”. The palette like the rest of his imagery is spontaneous and colourful. Though red is his favourite colour, he uses a variety of colours, picking them up randomly, or what lies in front of him at a given moment.

Quick with his work, Hem Raj can do a lot in eight or so hours that he spends on his own art practice every day. Working on several canvases simultaneously, he keeps his focus on the one painting in hand for each day. Beginning with preparing the base by covering the blank canvas with a coat of one colour, whichever is readily available, Hem Raj begins to play on the canvas. There is no preplanning or thought-out grammar involved in the work. No sketching either, prior to painting the canvas directly with a brush. “It is done entirely spontaneously”, claims the artist, as he allows the brush to take the paint on its course, any which way that it goes. With paint flowing in different directions, indiscernible imagery begins to take shape on the canvas. “If what appears on the surface does not appeal to me, I delete it, by removing the paint with my spatula”. Even this process of addition and deletion in the painting happens on its own, guided by the divine. “At times, the finished work surprises me too”.

Abstract organic lines, reminiscent perhaps of his early life encounters with tailoring or may be electrical work, appear here and there in his work recurrently. Various other symbols and geometric renderings make their way too on the canvases anew and fresh in each composition. He likes to finish painting the work in hand the same day “as it helps maintain a rhythm”. Engaging with tonality, the coloured stretches on his canvas come thick and fast and in an interface of tranquillity with aggression. Starting with a thin layer of paint, he moves on to painting in thicker layers. “I paint 15 to 20 layers of oil paint wet on wet, covering the whole surface and in quick succession, without allowing time for each layer to dry before putting the next one on top”. The artist explains that multiple laying in such a rapid progression, helps ensure that the subsequent layers do not weave into the lower ones, besides protecting oil paint from developing cracks. It also adds the right tonality and texture, to the structure and framework in his art scape.

Eternal Reminiscence

Hem Raj’s eternal reminiscence series in this second edition is expansive and rooted. The compositions mirror the artist’s spiritual bent of mind where the physical world perceived as an illusion appears to merge with all pervasive divine spirit and the surrounding natural phenomena. With its focus on meditation and inner contemplation, the artist taps into a realm of abstraction. Somewhat surrealist and beyond worldly realities, the featured paintings, encompass a wide range of styles. Beyond the confines of defined forms, Hem Raj’s eternal reminiscence artworks are filled in with different shapes, signs, markings and lines - straight or twisted or zig-zag, with calligraphic notations. There is text calligraphed with names of divinities in some paintings and symbols suggestive of temple bells and rain drops in the others. There are also suggestive motifs of birds in flight or plants swaying in the air. Metamorphic and imagined impressions of tantras, mandalas, creepers, and animals are incorporated in a primordial language of his own design. Painted in a wide spectrum of unrestrained colours, the palette in the series ranges from bright red, blue, green and yellow to some subtle markings painted in black and pastel shades. This approach endows the depicted paintings with an other-worldly spark and a soul. Also makes them more engaging and accessible.

Four Iconic Artists

(Shridharani Art Gallery, New Delhi, 29 October - 10 November 2024)

Yashodhara

Dalmia

Curator

As notions of feudalism began to dissipate, and an awareness of historical identity and the concept of a nation became part of the new quest for freedom in India, it became evident that modernism in art would manifest itself as a major vehicle for self-expression. Instead of the largely mimetic and picturesque works that had been popular and had immobilised art, the emerging forms began to be transformed into a vital and imaginative genre.

It was this encrusted modernity with its multiple levels of aesthetic codes, reflecting the diversity of the country, which became established and a forceful consciousness arose of a growing individualism and a powerful need for self-expression. In Bombay as well as in other cities, as groups of artists congregated to articulate their innovative beliefs, a strong and multiple form of modernism began to take place. In a rising nation it was the underbelly of existence that inevitably became the prime focus for the artists as the burgeoning life of the streets spilled out and created a vivid entourage of memory and metaphor.

While Euro-American modernity placed countries like India as the ‘other ‘and the ‘marginal’ they were at the same time dependent on the colonised, a result of interpenetration with the material and aesthetic notions of these countries. Displacing the notion of this modernity as pivotal then, we have to see that there was a fusion and the creation of a ‘Third Space’ where as the scholar Homi Bhabha emphasized the ‘difference is neither the One nor the Other, but something else besides, in-between’.1 Hence the multi-dimensional cultural forms which created the paradigms for non-eurocentric modernities and also emerged in India privileged this norm as significant and gained widespread popularity.

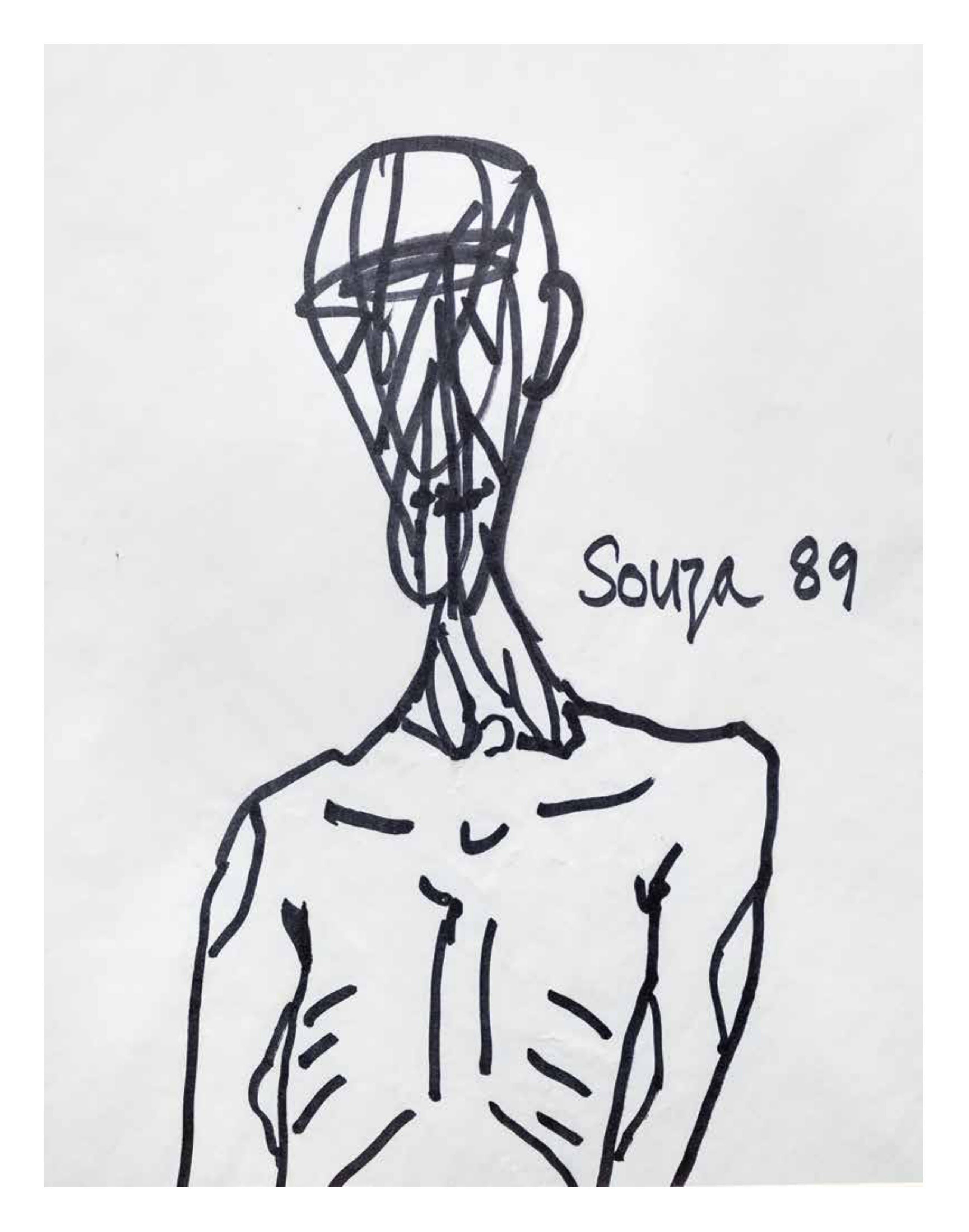

In Bombay, a group of artists gathered in 1947 to form the Progressive Artists’ Group in the very year that India gained Independence, and in their compelling endeavour for rooting modernism in their country presaged the very core of art in the nation. The group was initiated by the artist Francis Newton Souza [1924-2002] who with his audacious distortions of the human form and frank exposures of the body not only aroused a strong reaction but also created the tenor for modern art. The other artists in the Group consisted of M.F. Husain, S.H. Raza, K.H. Ara, S.K. Bakre and H.A. Gade and their primary objective was to propel a modernism which critiqued the outmoded practices of schools of art and rejected outright the revivalistic approach of the Bengal School.

With a new nation coming into being and with the onset of modern Indian art, it was Francis Newton Souza who could be said to be the generative source of this creative transformation. The Goan artist had not only founded the Progressive Artists Group in 1947 but created the syntax for Indian art with his devilish heads, nude and voluptuous women and apocalyptic landscapes which began to expose the seamier side of existence. These were images which were deftly made with few bold strokes and etched out the human physiognomy in all its disingenuity such as the work in this collection (oil on board,1957). In engaging with these, the artist was to make eminently modern forms which depicted contemporary life. Souza’s strict Catholic upbringing in Portugese Goa had far from making him a devout Christian, instead provoked him into being ferociously anarchic against the rigidities and the corrupt practises of the Church. His view of Christ was not that of a compassionate figure but of the vengeful God of Romanesque Churches in Spain.

Souza left for London in 1949 where he experienced the country’s post war angst and witnessed ravaged buildings and food shortages which cast their gloomy shadows. He found it difficult to exhibit his works and lived in a situation of penury. A few years of deprivation followed but after that the artist’s inherent talent began to be recognized. In 1954, he participated in the group show held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts where he exhibited along with artists like Graham Sutherland and Francis Bacon with whom his work can be said to have a correspondence. In infusing the dark mood of the post- war era Francis Bacon (1909-1992) for instance had exposed the human form with the hideous and the brutal underside of his personality. A meeting with the poet, critic and editor of Encounter, Stephen Spender also brought about his participation in an exhibition and would also lead to the publication of his autobiographical essay ‘Nirvana of a Maggot’ in Encounter the following year which won him further acclaim. This coincided with his solo exhibition in 1955 at Gallery One. Writing on this exhibition the famed critic John Berger wrote,’ How much his pictures derive from Western art and how much from the hieratic temple traditions of his country, l cannot say. Analysis breaks down and intuition takes over. It is obvious that he is a superb designer and an excellent draughtsman. I find it quite impossible to assess his work comparatively. Because he straddles several traditions but serves none’2 Souza’s manifestation of hypocrisy acquired depth and dimension, however, when he impasted on his papal exposition an adult revulsion of power and corruption. His manifestations of the grotesque resulted in heads which were to bare the canker within the soul as it were. The cold, soulless eyes for forehead, gnashing teeth for mouth and the face bounded by ferocious lines in a ridged, rocky terrain petrified by its own violence became his means of exposing the inner malevolence of the soul. In a work such as in this collection (oil on board, 1961), the denouement of the upper classes with their vestments of polite behaviour and their underlying corruption impacts the viewer. In time to come the foetus heads, as Souza would have them, became tubular, then dotted with wriggles and squibbles and finally composed of octagonal shapes connected with funnels. Many examples of these can be seen as part of this exhibition. Even as the heads became increasingly inventive in their devilish visage, they also began to lose some of the earlier energy and passion and veer towards design, though ingeniously composed. Yet in their heyday they were to arouse the sheer horror of man’s inhumanity to man.

Apocalyptic Landscapes

The landscapes made by Souza are diametrically different from the picturesque and calm vistas of conventional modes. The ingenuous rectilinear shapes which were made in splashes of vivid colour created an exploding vision of the holocaust and nuclear outbursts where instability became the defining mode. The houses seem to be bursting by seismic undercurrents which would tear things asunder erupting from within. In one of the works here (oil on canvas ,1964) the brilliant red structures are on the verge of falling into an abyss of nothingness as the firm outlines of houses slide downwards shaking the very foundation of polite society.

Souza’s Still Lifes such as Untitled, (oil on canvas, 1959) seem to move towards angles and positions which would draw from his experience of wider world and would frame his objects. These are far removed from the intimate comforts of home and glazed with the reflections of his diverse experiences. In his diverse experiments with gouache, pen and ink, mixed media, oil on canvas and board and chemical paintings Souza’s brilliant draughtmanship creates a world of burning embers and sizzling disasters which have a profound effect of disarming conventions.

The violence as well as tenderness which infuse his most rebellious works create elegiac renderings of the magnificent. It could be said that these forms not only questioned oppressive methods but also in their wiry lines and astringent compositions turned conventional notions of art upside down.

Subramanyan’s Subversions

Across the continent on the eastern side, at Santiniketan, the multiple oeuvres of the artist, K.G. Subramanyan (1924-2016) consisted of polymorphic works made in diverse media ranging from paintings, water colours and reverse painting on glass to murals, sculpting and even set designing. Of these we can take note of a splendid suite of glass paintings which took place in the eighties reusing the technique of the practice from colonial times, but subverting its content to sardonic, witty and humorous narratives of the present. Quite ingeniously the artist imbued these works with an erotic flavour, reflecting the Kalighat traditions and relaying it for the present.

Subramanyan’s imbibing of the Santiniketan methods where he trained and taught was ingrained in his teaching at the MS University, Vadodara influencing whole generations of students. Following this he moved back to Santiniketan where he lived and worked till his retirement when he settled down in Vadodara.

Polymorphic Portraits

The extension of boundaries in form and method lay at the core of Subramanyan’s works. In the artist’s polymorphic works the animated movement of the portraits creates the notion of time within the moment. In the present series this imbues the visage with a sense of mobility while remaining still. In doing so the ordinary person extends his boundaries beyond the finite to the notion of being extraordinary. Thus, in the work Ragini Vibhas (Reverse painting on glass, 2003) in the present series the forms are juxtaposed both horizontally and vertically laying the surface open to further narratives. The man and woman in Leela (Acrylic on canvas, 2011) seem to incite dialogues between themselves as well as create a gestalt of the back and front as plants, animals and birds foreground the planar dimensions of the painting.

As the artist Nilima Sheikh pointed out, ‘Subramanyan brings to service the notion of modular divisions, additive in nature. The attenuation of form is conditioned directly by format, by the exigencies of space in this modular construct. Contour has a forming function which parallels rather than completes the function of colour formulation. This dual forming is extended through a calligraphic flourish that activates negative spaces. And the structural grid of the modular divisions repeats itself in patterns, enlivening the surface. Conversely, localized surface patterning may extend itself to form the overall design. Subramanyan employed these devices not only to reduce the art-craft polarities he found detrimental to an understanding of either, but also to engage in the practice of art as a craftsman might.’ 5

It was at the Fine Art Fair held in Vadodara in 1972 that Subramanyan first designed toys which became a further extension of his language. Made of bamboo, leather and beads these puppet- like animal forms served to bridge the gap between art and craft as well as create new compositions. As Sheikh pointed out, ‘For Subramanyan the fair was the best occasion to vindicate his several obsessions: the mobility between art and craft practice, between studio exercise and working in situ, between painting and the physically more projective arts, between varying scales and different materials and finally, between art as serious business ---and as fun.’6

According to the

artist ‘I have always used a fluid kind of space but this is not necessarily

true only of the miniatures. It is characteristic of a lot of oriental

paintings. But I will not quarrel with miniature because after all what is a

miniature? It is a painting to be read. Generally speaking, what you call an

easel painting is an extension of the miniature. Later people got into a

conflict about whether a painting was to be read or whether it was there for

decorative purposes. An abstract image takes away the readability or keeps it

subservient. In any case when I paint, I try to keep these two things

together—the human drama and the generality of the image. I like to use various

devices like the polyptch where various incidents, complete in themselves are

grouped together.7

Ram Kumar’s Sombre

Forms

Ram Kumar’s (2024—2018) lonely, alienated individuals located within tattered houses and shabby streets created the awareness of the plight of the ordinary person in a newly emerged, developing but also traumatised nation. These forlorn figures with their gaunt faces and melancholy eyes such as the girl sitting with a pensive expression and her hands clenched in this collection, loomed large over the cityscape and provoked a deep empathy.

He was an accidental artist and yet reached great heights in his works. Ram Kumar’s early days were as a banker and later as a journalist with the newspaper Hindustan Times. In the meantime, he had joined Sarada Ukil’s evening art classes. He also wrote stories in Hindi about lower middle-class individuals and the sordidness of their lives which was faced by them with great fortitude. This provided him with a means of existence but his increasing involvement with art took him to Paris where he studied under Andre Lhote and Fernand Leger.

Ram Kumar’s stay in Paris was not an easy one but as he struggled to survive, he also learnt to sharpen his tools. ‘I told my father I wanted to go to Paris and study art there. He bought a ship ticket which was Rs.700 and then I reached Paris without any money.

The Paris years were known for the camaraderie Ram Kumar shared with artists like S.H. Raza and Akbar Padamsee. His training in Paris along with his association with the Mumbai based Progressive Artists Group and with the Delhi Shilpi Chakra, provided the necessary professional alignments which enabled him to sharpen his artistic tools.

Ram Kumar’s paintings of Varanasi are well known for their lucid interpretation of the pilgrimage centre. It was in 1960 that he visited Varanasi with the painter M.F. Husain to study the sacred city at close quarters and this would prove to be a watershed in his painterly oeuvre. The stay there resulted in a series of paintings where, while the bustle and energy of the city and its sharp contrast with life and death were predominant in Husain’s works, Ram Kumar’s tight cubes of human dwellings were packed together precariously as shown in this collection and seemed as if they might crumble even as death dissolves life. Although there is no human presence, Kumar’s Varanasi works are haunting evocations of human suffering as well as fortitude in their continued endurance against great odds. As he stated, ‘The place, the light in the place plays an important role. The gullies, after gullies, the widows, the old men waiting to die. Manikarnika ghat and the dead bodies. There is hardly any difference between the dead and the alive there. They are waiting to be cremated.’9

According to the artist, ‘I think personally when you come to analyse yourself then you think when you are making formative paintings. I think psychologically you are undergoing certain phases of your own problems and they conveyed something in your paintings, in your colours and forms and gradually when the changes take place within yourself too then I think the colours and forms become different. In earlier times they were very muted, black and white and greys but now they are lighter so now perhaps one is more free. One wants to have more freedom so one applies many colours and see how what sort of feeling they create. One is not committed by any colour.10

In his later years Ram Kumar’s brooding works see the emergence of wedges of reds and greens as he attains an even greater freedom with his colours. A twig, a bit of broken roof tile, would give a glimmer of the storm underlying the radiating surface. The sense of pain beneath the most sensuous of his strokes creates an ever-present concern with human existence.

Gaitonde’s Luminous

Depths

While being exposed to the works of Western modernists along with that of the Indian miniature tradition V.S. Gaitonde (1924-2001) developed a penetrating insight into form and colour which provided him with new painterly modes. These varied influences combined to develop his non representational vocabulary in the late 50s when he abandoned his figurative style. The earliest work however such as in this collection (Oil on paper, 1950s) were figurative, similar to Ram Kumar, albeit a lyrical description of the countryside and idyllic renderings of village belles.

The metier and substance of his works later was the painterly surface itself where the application of paint created a highly textured area with thick and thin paint balancing themselves to reflect light in a nuanced manner. In New York on a Rockefeller scholarship in 1964 his work further transformed when coming into contact with the Abstract Expressionist form of painting with its focus on all- over paint which was dripped or slashed on the canvas.

The school itself had become a marker for High Modernism and set about a ripple of possibilities in the painterly world. Indeed, he along with the artist Krishen Khanna had visited Mark Rothko’s studio and this proved to be a catalyst for his own emergence of tints over large expanses.

Gaitonde’s luminous colours would assume no shape and form and would evoke nothing other than themselves. It was the very surface which was the sensuous pre-occupation of the artist, and he modulated paint on it as if it were his object of passion. The artist’s colour surfaces are translucent, creating almost an underwater ambience with beams of light penetrating the depths. His radiant reds with flashes of light such as the one in this collection (Oil on canvas 1991) would create a conglomeration of colour and strokes which seemed to rise from unknown depths. His swabs of paint would regurgitate from the very bottom like the limitless ocean which he had sat across and ruminated for hours from his studio at Bhulabhai Desai Road in Mumbai. The white stroke on white for instance could create the textured tonality which provoked the profound essence of creation. At the centre of his paintings lay the belief in bringing this to the fore with its boundless possibilities.

The artist himself contradicted the fact that he was an abstract painter and always referred to his own paintings as being ‘non-objective’. In his later works and after a serious accident in the mid-80s his work developed a painterly hieroglyphic and calligraphic system of signs and symbols which intuitively recalled the hallowed grace of the universe. An artist prone to meditative silence he tended to dwell on both Zen philosophy and ancient beliefs including calligraphy.

The artists who came to the fore and continued with their creations were to influence ensuing generations over the century. Their styles, and also importantly their beliefs, formed the path that was later taken and evolved by modern and contemporary art in India. From Souza’s diabolical humans which questioned corruption, to Subramanyan’s expressive delineation of street life, Ram Kumar’s tightly-wedged houses which muffled the surface in despair and Gaitonde’s emblazoned paintings rising from the depths we have the emergence of a monumental art for the country. The language thus created became varied and distinctive in shapes and colours as an underlying unity of beliefs knitted it together for the people as a whole. In the struggle to carve a meaningful path which reflected contemporary life, the artists’ heroic attempts became symbolic of the nation’s own impassioned means of existence.

NOTES

1. Homi K. Bhabha,

The Location of Culture London and New York,1998

2. John Berger, New

Statesman, date unknown

3. F.N. Souza,

‘Cultural Imperialism,’ Patriot Magazine, February 12,1984

4. K.G. Subramanyan, Santiniketan, the Making of a Contextual Modernism catalogue of the show at NGMA curated by R.Siva Kumar, NGMA, New Delhi, 1997

5. Nilima Sheikh A Post-Independence Initiative in Art, Contemporary Art in Baroda, edited by Gulammohammed Sheikh, Tulika, New Delhi 1997 p. 121

6. Nilima Sheikh,

Ibid, p.102

7. Interview with

the author, Mumbai, March 1990

8. Interview with

the author, Delhi, December 2007

9. Interview with

the author, Delhi, December 2007

10. Interview with

the author, Delhi, December 2007

11. ‘Painting as

Process, Painting as Life ‘Solomon R Guggenheim Museum,

New York, from

October 24, 2014, to February 11, 2015

Presents

Tales Of Transcendance

Dr. Geeti Sen

The paintings exhibited here bring to us some rare and lesser-known aspects in the work of celebrated artists. The majority of Amrita Sher-Gil’s paintings in Paris depict posed studio models, portraits and self-portraits. Her choice to return to live in India was deliberate, and she stated once that in India ‘lay her destiny as a painter’. She responded with different sensibilities to the Indian environment. On returning to India, she painted the hill men and women of Shimla, the peasants of Punjab and Uttar Pradesh.

In

her short-lived career as an artist of just nine years, she accomplished more

than do most painters. Born of a Sikh father and Hungarian mother, Sher-Gil had

imbibed the cultural sensibilities from both parents. Her work reflects radical

changes from the three years when she studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in

Paris, after which she returned to India in 1934. From the beginning however,

she knew that she would be an artist. She wrote:

It seems to me that I never began painting, that I have always

painted. And I have always had, with a strange certitude, the

conviction that I was meant to be a painter, nothing else.

Returning to India, Amrita visited her ancestral home in Amritsar, and then her uncle’s vast estate in Saraya. A water colour dated to 1936 suggests her explorations in rural India, focusing on a boy on a swing with his mother seated beside him. The sloping ground of the earth with the impressionistic rendering of trees and a bullock cart introduces a sense of perspective, from the training received in Paris. So also, the muted coloring of the scene is Western rather than Indian.

Another

water color of about this time is again impressionistic in technique, but

richly colored in delineating the warm browns and greens of the Indian

landscape. This composition distinguishes three separate areas of the

background and foreground introducing again the Western perspective. A third

water colour focuses on the house which takes up most of the picture space,

thus reducing the idea of depth and perspective.

These compositions are Amrita’s early explorations in representing the Indian landscape. Her letters to her mother, her sister Indu and to the critic Karl Khandalavala describe her travels through India in 1936, her appreciation of the colossal cave sculptures at Ellora and the murals at Mattancheri, and her meetings with extraordinary people such as Malcolm Muggeridge, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu. She was arrogant in her dismissal of contemporary painting in India, and she was influenced by the stylistics of Mughal painting.

In June 1938 Amrita left India for Hungary, and much against her parents’ wishes she married her cousin Dr. Victor Egan. By then she was over twenty-five and wished to be independent of them. Several Indians were keen to marry her, but she was reluctant to do so as she felt she could never be an ideal wife. She felt that Victor could accept her on her own terms, primarily as an artist.

One year later in 1939 she painted the portrait of the man she married, which may be her only portrait of him. Victor Egan appears in elegant attire by wearing a dark purple cape over his shirt, with a slight smile on his face as he smokes a cigarette. Sher-Gil was an adept in painting portraits, and she had painted several commissioned portraits for which she received payment. She also made several self-portraits in different poses. This picture however is quite different as it was not commissioned, rendering an informal and sympathetic study of Victor Egan. It is a rare work, returning to Western techniques in realism, as would be natural in such a portrait. As she died in 1941, this may have been Sher-Gil’s last portrait.

Jagdish Swaminathan was a revolutionary artist whose ideas stirred the art world to make a dramatic impact in the 1960s. He aspired to formulate a new visual language which would be rooted in the social and cultural context of his times. He was deeply critical of the principles of modernism, and the imitation of Western styles and techniques. Equally, he was opposed to influences from traditional art, as was to be found with the Bengal school of artists.

In the 1950s he was already writing as an art critic. During these decades he was a political organizer and agitator, who joined the Congress Socialist Party in 1945 and later the Communist Party in 1947. His charismatic personality had much to do with the founding of Group 1890. This group was born in 1962 as a collective of twelve artists who were chiefly from Delhi, Baroda and Bombay. At the heart of their formation was the urgency to re-examine the current state of art, and to innovate a new language which could be described as indigenous modernism.

Their

first and only exhibition was held in October 1963 at Rabindra Bhavan in Lalit

Kala Akademi, Delhi. With much fanfare it was inaugurated by Pandit Jawaharlal

Nehru, with an emotional speech given by the poet Octavio Paz who later became

Mexico’s ambassador to India. It was

with the persuasion and help of Octavio Paz that in 1966 Swaminathan started

his journal called Contra. The Manifesto of Group 1890 began by rejecting not

just the canons of Indian art, the Bengal School and academic realism, but also

the expression of modernism practiced in the 1950s which bore strong influences

from Western art.

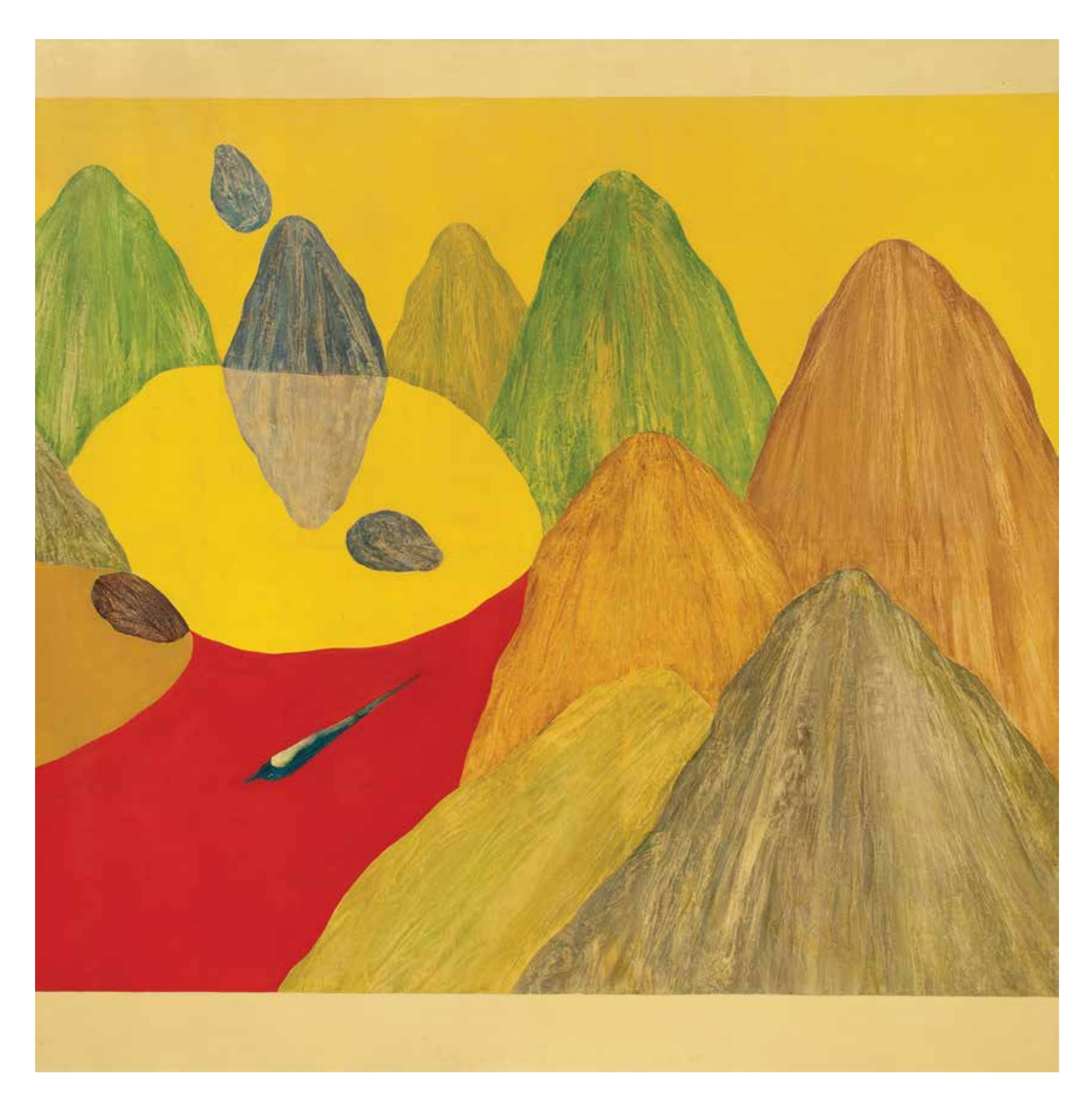

In his paintings Swaminathan was deeply inspired by the indigenous art of the Murli and Marli and Warli communities from central and western India. His art absorbed the vibrant colours of earth reds and browns with daubs of yellow and black which appeared and were painted on the walls of their homes. A line of triangles, squiggles and symbols with some times the imprint of hands are brought together in a new visual language, raw and bold in expression -- to create a visual experience unparalleled in the art of his contemporaries.

By the mid-1960s he began to explore the relation of colour to space. He studied Pahari miniature traditions, which are reflected in his series titled Colour Geometry of Space. This was followed by his series on Bird, Mountain, Tree and Reflection, which are to be seen in two images in the collection of the Progressive Art Gallery. The arbitrary demarcation of space, with no suggestion of depth or perspective, creates a radically new idiom. Mountains or rocks are introduced in different hues of blues, beige and green, punctuated by the presence of a bird or a flower. Four of this series of paintings are to be seen here in this exhibition, each of them creating different experiences.

In 1982 Swaminathan was invited to establish the Roopankar Museum of Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal. Significantly, in setting up these galleries he gave equal importance to contemporary urban art as to the tribal art of the adivasis. These were located in two separate wings of the museum which was designed by the architect Charles Correa. Swaminathan continued to serve as Director of Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal till 1992, and he died in 1994.

Swaminathan’s own works of this time reflect the inspiration from tribal art, to be seen in his abstract compositions in mixed media from the later 1980s and early ‘90s. Dots and lines, squares and the triangle are brought together in differing expressions, to formulate an elementary language which aspires to an absolute purity in vision. With these drawings his aim was to attain freedom, spontaneity and individuality. Many contemporary artists in India have created their own visual language, over the seventy-five years since India gained Independence. None of them have been able to defy the visual conventions in art as he did, to create a radically new experience.

Prabhakar Barwe’s abstractions are often minimalist, surprising us in their variations in colour and also in medium. His works vary from using enamel to wood to gouache on paper. Unexpectedly, he introduces an anthropomorphic figure in almost the centre of the composition, flanked by the curving arch of a circle and strips of canvas. Or he can assemble geometric forms together in blue and beige and black – with no narrative being told except the wonder of their creation. He can place a figurine lying horizontally, with a foot and fragments of a female form sketched in below. In another the head of a horse with its fore legs becomes visible, floating in a vacuum of space with forms which are undistinguishable.

The artist is inviting his viewers to complete each painting, to reflect on forms that are deliberately left incomplete and floating in space. There are no precursors for such compositions in Indian art, or for that matter, in contemporary art in the world. Through his images Barwe was aspiring towards attaining a sense of serenity, as well as a sense of balance and purity. His introverted gaze as one could call it, aspires towards the spiritual.

Apart from these abstract compositions is another image entirely different in its sensibility. Barwe creates an elaborate design with two concentric circles enclosing a six-pointed triangle, flanked by smaller geometric patterns. Boldly printed in contrasting colors of black, red and white, this work inspired by Tantric forms is a Sri Yantra, designed for commercial use on silk by a handloom company.

Barwe made several patterns for commercial use, in sharp contrast to the subtlety of his own abstract formulations. Their existence compels us to reflect on his life’s journey, which followed two different trajectories which are almost contradictory in their aesthetics: of his own abstract compositions, and of commercial designs which were commissioned with a different purpose. The collection in the Progressive Art Gallery offers us rare insights into these two polarities in the work of Barwe.

Ganesh Pyne’s paintings arise from a private, inner vision which is poetic rather than realistic. He captures the psyche of Bengal through his enigmatic images of the fisherman casting his net, the river, the fountain, the lamp, the horse and rider. He creates his own mythology, relying on medieval lore rather than his immediate everyday life. As a lonely child his imagination was set alive by tales recounted by his grandmother on dark nights, tales from the medieval mangalas and charya padas. In his painting titled Encounter in the Twilight Zone forms dissolve from tangible reality, from the known and familiar into the unknown.

He wove the fabric of his paintings from the haunting songs of the Bauls, the ‘mad mystics of Bengal’ as they have been called. He represents them in this collection, holding the single string instrument of the ektara with which they sing and dance. Their songs are about the wonders of creation: of journeys along the river in spate and the storm brewing, of the forest and the tiny lamp glowing in the darkness. The Bauls sing in ecstasy, using the metaphors of the lamp and the river.

My heart is a

lamp, floating in the current

drifting to what

landing place I do not know…

Darkness moves

before me on the river…

Both day and night

the drifting lamp moves

searching by the

shore..

Sung by Baul

Gangaram, quoted by Edward Dimock,

The Place of the Hidden Moon, Oxford University Press

The collection in the Progressive Art Gallery offers us a range of paintings from 1957 to the year 2000, following the evolution of his work from early experiments to his mature work. The Money Lender from 1957 already focuses on a single figure seated with his hookah and wooden money box, transforming a mundane subject into one of poignancy. The forms dissolve into tones of yellow, white and beige/ browns, with touches of unexpected green in the face and elsewhere. This richness of palette would be unusual in his later work which restricts itself to fewer and more subtle colours.

Abhimanyu, painted in the year 2000 in tempera, ranks among the finest compositions by Pyne in his mature style. The youngest hero from the Mahabharat appears before us armed with a mighty bow that extends to the entire height of the canvas, with a sheaf of arrows hung from his right shoulder and a dagger dangling from his hip. He is poised and alert, ready for action in the battle which is about to ensue.

Abhimanyu is an arresting and a disturbing figure as he looms up clad in his blue armour, against a background of crimson blood red which hints at the tragic consequences which would follow. As related in the Mahabharat, while still in the womb of his mother Draupadi, he had learnt of the means of how to enter the complex web of the battlefield, the Chakravyudh; but he had not learnt how to exit from the field, which would prove to be his tragedy.

Pyne has chosen to represent the greatest of all heroes in the Mahabharat in his moment of glory; but in that same moment, he appears to be vulnerable. A strange radiance of light shines from within him from no given source, glowing on his face, his broad shoulders and his hands. It is Pyne’s use of light above all else which empowers and transforms his figures, so that beauty is rendered with the realization of pain.

The technique of gouache used in this image of Abhimanyu was Pyne’s forte which he mastered, a technique in traditional miniatures rarely used by contemporary artists. It is an elaborate process which takes time and considerable patience. It is this technique which builds up the surface and texture of the canvas, so that the forms seem to be composed of a thousand particles, like algae or seaweed in the deep ocean.

His representations of women from the year 2000 are not Titled. Their beauty is enhanced by that mysterious glow of light Which outlines the contours of the saree and the hand, the forehead, the lips, the slender necklace which slips down her neck. Light radiates from within these figures, embodying them with a subtle, insistent radiance.

The Metascapes

by Akbar Padamsee are grandiose and sweeping in their vision. They transcend

the conventional representation of specific sites and geographical locations.

He had remarked on this by asserting:

I’m not interested

in location of landscape. My general

theme is nature –

mountains, trees, the elements, and

obviously one is

influenced by the environment, but I’m not

interested in

painting Rajasthan or the desert of whatever (place)…

Padamsee’s paintings evoke an experience which evokes expression and sensation, rather than the cognitive recognition of a landscape. This idea of the ‘sensation’ caused by physical matter can be felt in the two Metascapes in the collection of the Progressive Art Gallery. He developed several devices to suggest the idea of expansion, mirror images being one example. He limited his palette to using just a few primary colours, where the sustained impact of red can be almost violent. His work introduces geometric forms which result in an impact that is both dramatic and dynamic.

The idea of using

the Sun and the Moon in my Metascapes

originated when I

was reading the introductory stanza to

Abhijnanashakuntalam,

where Kalidasa speaks of the eight

visible forms of

the Lord.. the sun and the moon as two

controllers of

time.. water as the origin of all life, fire as the

link between man

and god and the earth as the source of

all seed… when the poetic meaning is superimposed upon

the sign a new

form arises which belongs to the mind of the

artist, not to the

natural environment.

In

1969 Padamsee received the Nehru Fellowship for Visual Arts. He decided to make

a film with the funds, and to set up an interactive workshop called the Syzgy

project which involved other artists. He was the most intellectual artist among

all his contemporaries, and he introduced a geometric foundation to his

Metascapes. He was inspired by the

paintings and the writings of the artist Paul Klee. He would quote the passage wherein Klee would

compare a work of art with the growth and the transformation of a tree.

From the root the

sap rises up into the artist, flows through

flows to his

eyes. He is the trunk of the tree and

overwhelmed

by the force of

the current, he conveys his vision into his work.

In full view of

the world, the crown of the tree unfolds and

spreads in time

and space, and so with his work. Nobody

will

expect a tree to

form its crown in exactly the same way as its

root. Between above and below there cannot be

mirror images

of each other…